The struggle of being an immigrant can be a challenging experience, but for many female immigrants, the struggle goes beyond the difficulties of adapting to a new country.

In some cases, they can find themselves held in prison under immigration powers, which can have a profound emotional impact on their well-being. In this blog post, I will tell you my story and explore the emotional struggles that I faced.

Female immigrants can be detained for various reasons, such as entering a country without proper documentation, overstaying a visa, or being sentenced for a crime.

While the reasons for detention may vary, the emotional toll it takes on these women is often similar. People can be detained in Immigration Removal Centres or in prisons, restricted by prison rules.

At the end of a prison sentence, British people are released but those classed as “foreign”, are punished twice more for their crime. First with a prison sentence then with detention and potential deportation – regardless of their rights to stay in the UK.

Entering a prison for the first time is an overwhelming experience. The atmosphere is tense, the surroundings unfamiliar, and the uncertainty of what lies ahead is daunting.

You will undergo a comprehensive search, potentially including a strip search where you must remove all your clothing. Following that, you will be seated in a specialised chair known as the BOSS chair, which ensures that no electronic or phone devices are concealed within your person.

I was shocked to see the chair, it looked like an electrocution chair from a horror movie. This process is humiliating and intrusive but you don’t have the option to refuse so it is best just to get on with it. I am now not who I am, I am a number, everyone there is a number.

The nights in prison can be likened to being in a psychiatric hospital. The sounds of doors banging, people crying, hauling and even laughter fill the air, creating an unsettling environment. The concept of time becomes blurred, as it is difficult to determine when one arrived in this new world.

The cell itself is a far cry from the comfort of home. It consists of a bunk bed, a panel as

a table, a sink and a toilet without a lid, both mounted in plain sight without any privacy

door. The light is dim, flickering and covered with a sanitary towel, adding to the overall gloominess of the space. The bedding provided was a smelly old duvet, devoid of any cover, and adorned with countless blood stains. I lost all my energy and fell asleep with tears in my eyes.

You are kept in the same cells whether you are serving a prison sentence or are there under immigration powers. You can be locked behind doors in your cell more than 23 hours a day, most of the time with others. Very often there are staffing issues and you are locked in all day.

When you’re a prisoner there are more opportunities to get out of your cell such as work, prayer or education but not all these are available if you are detained by the Home Office so you spend even more time in your cell.

Being an immigrant in a foreign country can be challenging, but for female immigrants who find themselves in prison, the emotional struggles can be even more profound.

Female immigrants in prison often feel isolated due to a combination of factors. Firstly, they are separated from their families and support networks, which can be devastating for their emotional well-being. Additionally, language barriers can make it difficult for them to communicate and connect with other inmates or prison staff. This sense of isolation is further exacerbated by cultural differences and the unfamiliarity of the prison environment.

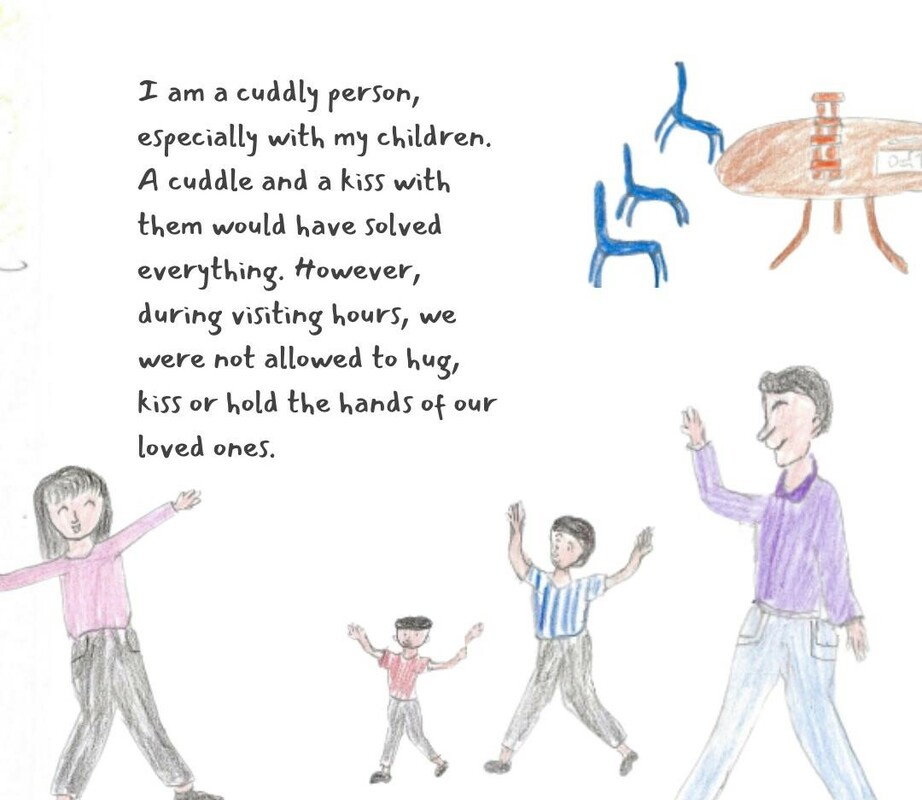

I know this first hand. I am a cuddly person, especially with my children. A cuddle and a kiss with them would solve everything. However, during visiting hours, we are not allowed to hug, kiss or hold the hands of our loved ones.

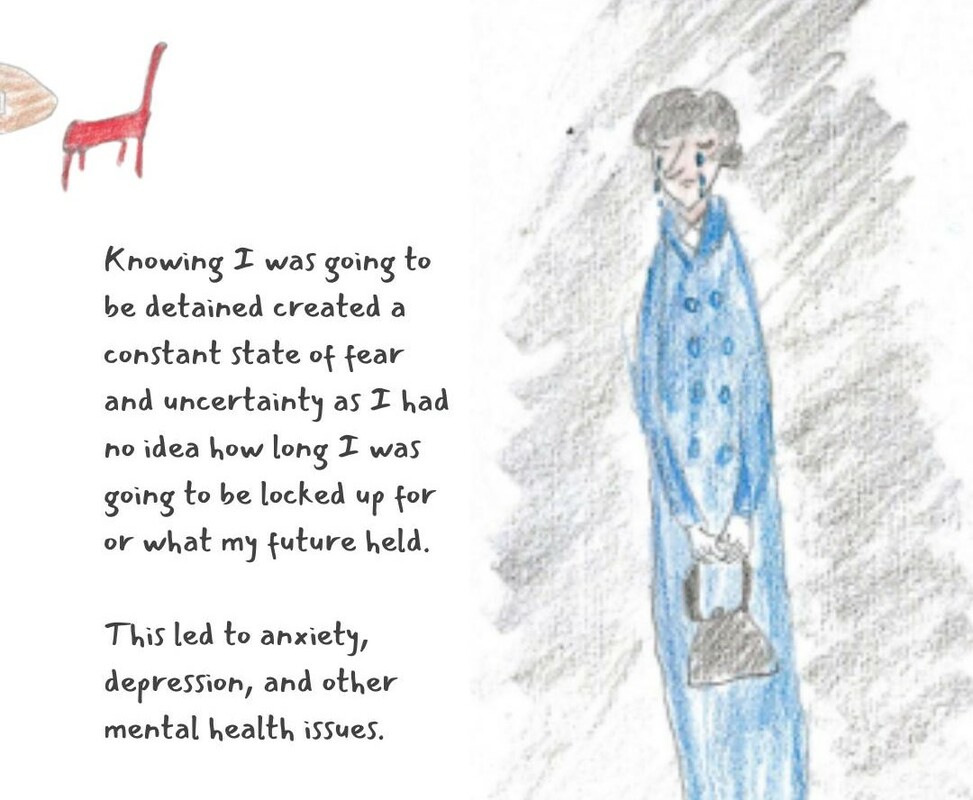

Knowing I was going to be detained at the end of my sentence created a constant state of fear and uncertainty as I had no idea how long I was going to be locked up for or what my future held.

This led to anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues. It is like a sentence on top of another sentence but it is worse as you never know when you will be released.

I started to hurt myself and attempted suicide multiple times. I witnessed others self harming and attempting suicide most days. It had become a norm sadly - leading to some twelve-ambulance call-outs a month.

Female immigrants held in prison often face limited access to resources that can support their emotional well-being. Mental health services may be inadequateor non-existent.

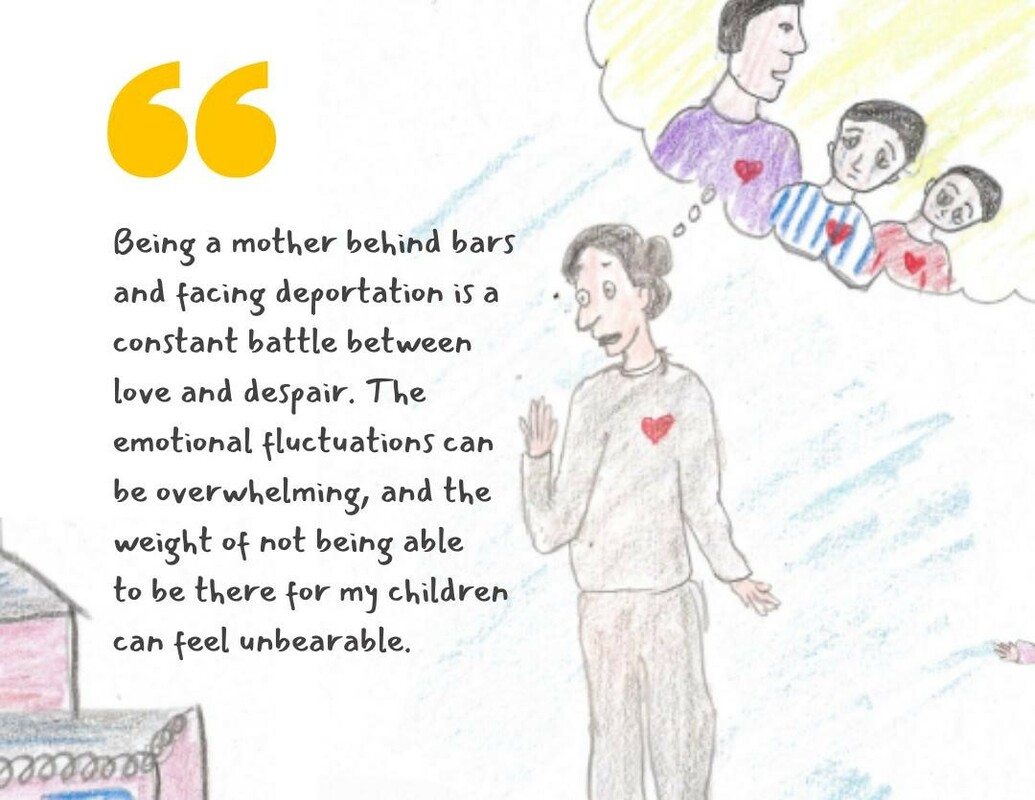

Being a mother behind bars and facing deportation is a constant battle between love and despair. The emotional fluctuations can be overwhelming, and the weight of not being able to be there for my children can feel unbearable.

Language and cultural barriers further exacerbate emotional struggles as they can make it challenging to express needs, concerns and navigate the immigration bail process. Additionally, cultural differences may result in misunderstandings and a sense of alienation.

Where I was, there were only a handful of us facing deportation. All of us spoke different languages. But we looked after each other when needed. We were united in our diversity, bound by our shared experiences, and driven by our dreams.

Life in prison can be tough. The monotony, the isolation, the lack of freedom—it can really take a toll on a person. But sometimes, in the most unexpected places, you find a glimmer of hope, a ray of sunshine amidst the darkness. For us, that glimmer came in the form of food and communication.

When you're far away from home, the taste of your mother's cooking can transport you back to a place of comfort and familiarity. We longed for that feeling, so we decided to chip in and create a makeshift canteen where we could try to assemble each other's traditional dishes.

It was a way to preserve our culture, to share a piece of home with one another. Food has a magical way of bringing people together. As we sat around the table, sharing our meals, we formed a bond that transcended language barriers and cultural differences.

We laughed, we cried, we shared stories of our past and dreams for the future. In those moments, we were not just inmates—we were a family. Our body language became more expressive, more confident. We no longer needed words to understand each other.

Many of our fellow immigrants were illiterate or struggled with English, making it difficult for them to navigate the complex world of immigration law, paperwork and applications. I saw an opportunity to lend a helping hand. I became their translators, their scribes, their advocates. I filled out forms, wrote letters, and made sure their voices were heard.

One of my biggest fears was the possibility of being deported. If that happened, my life would crumble before my eyes. My husband would divorce me, leaving me with no money, no job, and no chance of having custody of my children. The thought was paralysing.

So, picture this: you're stuck in a legal limbo, anxiously waiting for your immigration bail hearing. It's like being on a never-ending rollercoaster ride, except you're not having any fun and there's no cotton candy in sight.

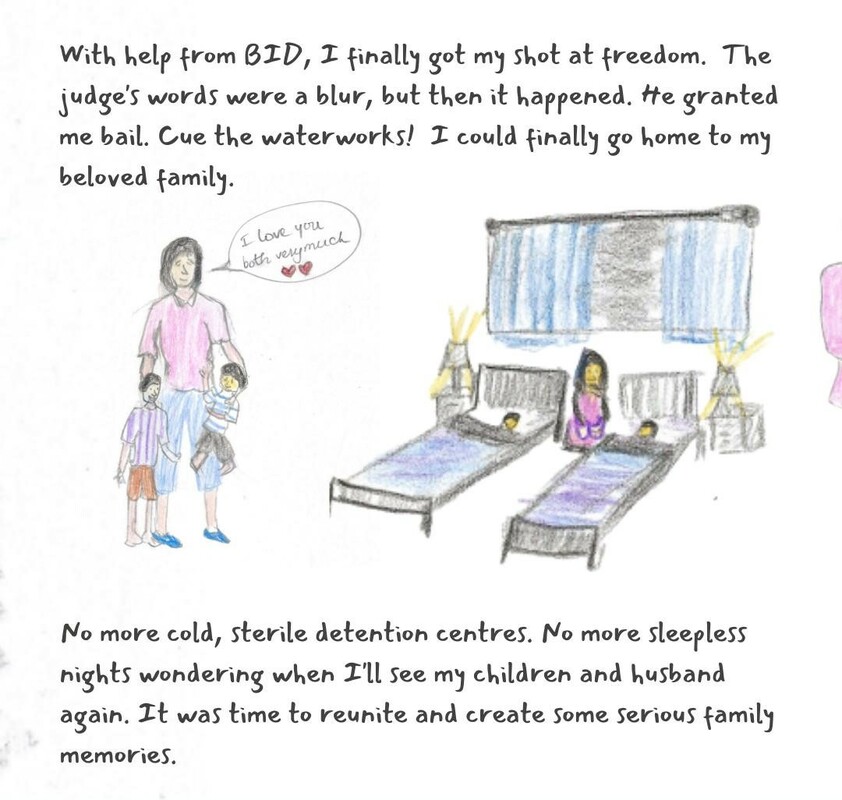

But fear not, my friend, because with help from Bail for Immigration Detainees, I finally got my shot at freedom. There I was, sitting in the video room, feeling like a fish out of water. The judge's words were a blur, but then it happened. He granted me bail. Cue the waterworks! I couldn't hold back the tears, and neither could one of the prison staff members sitting beside me.

We cried together, like a couple of emotional wrecking balls. With the judge's decision, I could finally go home to my beloved family. The feeling was indescribable, like a weight had been lifted off my shoulders. No more cold, sterile detention centres. No more sleepless nights wondering when I'll see my children and husband again. It was time to reunite and create some serious family memories.

Now, I know what you're thinking. "But wait, what exactly is a bail hearing?" Well, my friend, let me break it down for you. A bail hearing is like a golden ticket to freedom. It's a chance for the judge to decide whether you can be released from detention while your case is ongoing. And let me tell you, that decision can make all the difference in the world.

Thanks to BID, I had the support and guidance I needed to navigate the legal maze. They were my guardian angels, swooping in to save the day. Without them, I would have been lost in a sea of legal jargon and paperwork, at the worst point of my life.

They were my go-to resource, answering all my questions and providing a shoulder to cry on (literally). So, if you find yourself in a similar situation, don't despair. Reach out to organisations like BID, who are there to lend a helping hand. Trust me, they are godsend people. They'll fight tooth and nail to ensure you get the fair treatment you deserve.

Now, I'm back where I belong, surrounded by the people I love. The journey wasn't easy, but with a little help and a lot of determination, I made it through. So, if you're facing a bail hearing, remember that there's hope. And who knows, you might just find yourself shedding tears of joy, just like I did.

*We have used the pseudonym Eve at the authors request.

Eve is currently developing the drawings she made for her children which she was detained (pictured here) into a children's book to help others in the same situation. Watch this space for more news on that soon.